What Is a Term Sheet? A Complete Startup Founder’s Guide

The Term Sheet in 60 Seconds

A term sheet is a non-binding document that outlines the key terms of a proposed investment, usually at the fundraising stage.

Who uses it and when: Venture capitalists, angel investors, and founders use term sheets during fundraising, typically after initial due diligence and before drafting legally binding agreements.

What Is a Term Sheet? Term Sheet vs Contract

A term sheet isn’t a contract, but it sets the stage for one. Think of it as a deal summary, used to align founders and investors before lawyers get involved. It lays out the proposed terms of investment or acquisition so that both parties can align before diving into heavy legal work.

In startup fundraising, a term sheet outlines the who-gets-what of your next round: valuation, equity, board seats, investor rights, and more. It’s also used in M&A deals to detail price, control terms, and founder outcomes before final documentation.

When it appears: You’ll usually see a term sheet after you've pitched and the investor is serious, but before the legal team gets involved. It’s a high-trust signal, but still a prelude.

What a Term Sheet Is Not

A Term Sheet sets the stage, but it’s not the final act. Here’s what it isn’t:

- Not a binding agreement: Core terms aren’t enforceable, but clauses like confidentiality, exclusivity, and jurisdiction often are.

- Not a definitive agreement: The real paperwork—SPA (Share Purchase Agreement), SHA (Shareholders Agreement), or Convertible Note, comes later.

- Not a legal promise to invest: Even with signatures, investors can walk. And so can you.

It’s an alignment, not a commitment and that gives you room to negotiate smartly.

Why Term Sheets Exist (and Why They Matter in Fundraising)

Term sheets are a critical first step in any startup raise. They establish the core terms of the deal before anyone gets buried in long-form legal work. Here’s why they matter:

Speeding Up Negotiations

Instead of debating every clause inside a full contract, both sides can align quickly and decide whether the deal is worth pursuing.

Signaling Commitment

Sending a term sheet signals the investor is ready to lead, commit legal resources, and move forward. It’s the moment interest becomes action.

Preventing Misalignment Early

Term sheets force conversations about the things that matter most such as valuation, control, liquidation preferences, before the legal bill starts climbing..

Reducing Legal Fees Later

Getting the big decisions right upfront makes the definitive documents faster to draft, easier to review, and cheaper to close.

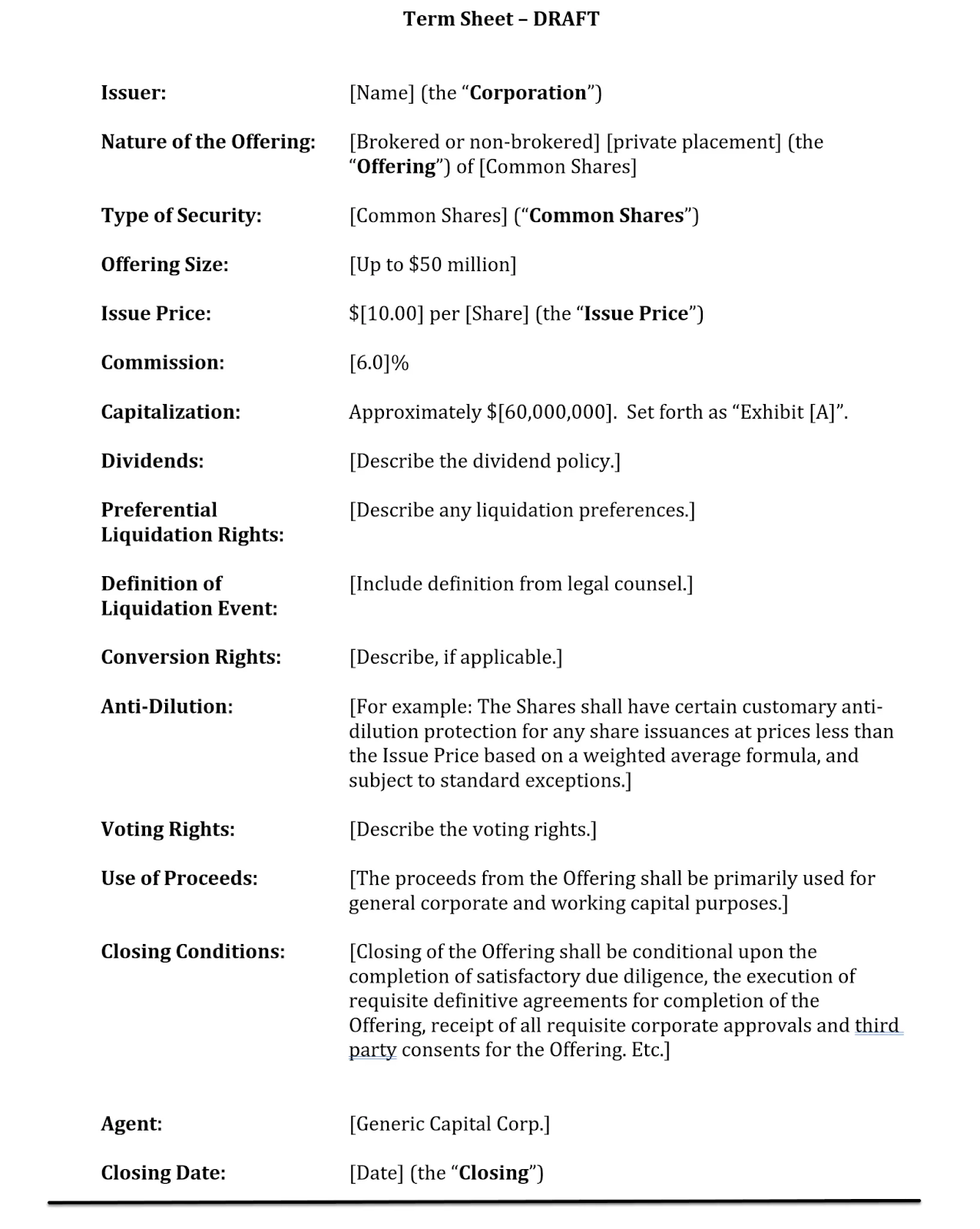

Anatomy of a Term Sheet

Every term sheet is a high-stakes checklist. What you agree to here will shape your cap table, control, and exit potential for years to come. Let’s break down the key components.

Valuation Terms (Pre-money vs Post-money)

Valuation terms define what your company is worth and what that means for dilution.

- Pre-money valuation is what your company is worth before new investment.

- Post-money valuation adds the new capital to that number.

Always clarify which one is being used. For instance:

A $10M pre-money valuation with a $2M raise = 16.7% dilution

A $10M post-money valuation with a $2M raise = 20% dilution

The difference can cost you real ownership.

Equity Split & Cap Table

This outlines who owns what post-deal, including founders, investors, and the employee option pool.

Watch for the “option pool shuffle.” If the option pool is carved out before valuation, founders take the dilution, not investors.

Investment Amount + Tranche Structure

This defines how much capital is being invested and whether it comes in one go or in milestone-based tranches.

Tranches tied to vague goals are risky. Push for objective milestones, like shipping v1 or hitting on-chain metrics not subjective investor criteria.

Liquidation Preferences

In an event where the company decides to liquidate due to sale, this determines which shareholders get paid out first.

Common scenarios:

- 1x non-participating: Investors get to claim investment on priority over common shareholders.

- Participating: Rights of non-participating + pro-rata share in the pool available for common shareholders.

- Capped participation: Limits the upside of participating preferences.

Participating preferences can heavily tilt exit outcomes. Make sure you understand waterfall mechanics before signing.

Board Composition & Control Rights

Specifies how many board seats investors get and what decisions need board or investor approval.

Board control = long-term leverage. Aim for founder-majority or include an independent seat. Be cautious with veto rights, they can block future raises or product pivots.

Pro-rata Rights

Gives investors the right to maintain their ownership in future rounds. It’s usually standard for quality investors. But avoid giving blanket rights, limit them to major investors who plan to stay involved long-term.

Anti-dilution Clauses

This clause protects investors if you raise a future round at a lower valuation.

- Weighted average: Investor’s ownership adjusts proportionally.

- Full ratchet: Investor’s price resets to match the new round, usually very aggressive.

Avoid full ratchet clauses unless heavily negotiated. Weighted average is the more balanced clause used.

Drag-Along & Tag-Along Rights

- Drag-along: If majority shareholders sell, they can force others to sell too.

- Tag-along: Minority holders can sell on the same terms if the majority exits.

Larger investors typically push for drag-along to ensure exit control, while smaller investors tend to ask for tag-along to protect their downside.

Vesting Schedules & Cliffs

It outlines how founder and team equity vests over time. The standard is 4 years with a 1-year cliff. Even founders should ideally be on a vesting schedule. It signals long-term commitment and protects the company if someone exits early.

Founder Restrictions / Leaver Clauses

It defines how equity is treated if a founder leaves, voluntarily or not.

Push for fair definitions. For example "Bad leaver" should mean misconduct, not disagreement. Avoid vague terms that let investors reclaim equity too easily.

Exit Terms & Triggers

They give investors certain rights in the event of an exit like veto power to block certain actions or decisions by the company, forced sale provisions, or return minimums.

Watch for low-value trigger thresholds or unilateral exit rights. Make sure exit clauses align with your long-term roadmap, not just investor timelines.

Exclusivity

It prevents you from talking to other investors while the term sheet is active.

Try to limit exclusivity to 2–3 weeks. Longer periods can freeze your momentum and reduce optionality.

No-Shop Clause

It’s quite similar to exclusivity and prohibits you from seeking or accepting other offers.

This is a standard clause, but time-box it. Don’t lock yourself out of better terms if this deal doesn’t close fast.

Confidentiality

This restricts both parties from disclosing deal terms or sensitive information.

It’s normal and expected, but review how "confidential information" is defined. You want clarity on what’s protected, and what isn’t.

Optional Conversion Terms

Relevant in convertible note or SAFE structures. It specifies how and when the note converts to equity.

Pay attention to conversion caps, discount rates, and maturity dates. These numbers directly impact future dilution.

Governing Law & Jurisdiction

Defines which legal system governs the agreement and where disputes are handled.

Align this with your company’s objectives.

Each clause is a lever. Together, they shape the deal and your ability to build, raise, and exit on your terms. GVRN gives you the clarity and tools to negotiate them with confidence.

Who Drafts the Term Sheet?

Investors are typically the ones to initiate a term sheet, especially when your project shows strong traction or outsized potential. It’s their way of moving fast to secure the deal. But just because they draft it doesn’t mean you take it as-is.

VC-Led vs Founder-Led

Most priced rounds (Seed to Series C) come with investor-prepared term sheets. These are often templated based on the fund’s past deals, risk appetite, and preferred terms.

Founder-led term sheets are less common but is an increasingly smart thing to do, especially when:

- You’re raising smaller checks without a clear lead

- You’re dealing with syndicates, angels, or DAOs

- You’re operating in founder-favorable ecosystems

When to Use Standard Documents?

If you're pre-Series A or raising from friends, angels, or early DAOs, start simple:

- SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) – YC standard

- Convertible Notes – debt that converts into equity later

- Series Seed templates – lawyer-reviewed, fast-track for early rounds

These work best for straightforward raises. If your deal includes tokens, multiple entities, or cross-border investors, standard documents won’t cut it.

Do You Need Legal Review?

Yes, because even non-binding documents can carry real risk. Legal review at the term sheet stage helps flag high-impact clauses (like liquidation, control, or anti-dilution), suggest protective edits, and prevent costly misalignment later.

Common Pitfalls and Mistakes

Term sheets move fast, and that’s when key details get missed. Here are four mistakes founders can’t afford to make:

- Overemphasis on valuation: A high headline number means little if it comes with participating prefs or board control that cuts your upside.

- Ignoring liquidation preferences: These decide who gets paid first. One bad clause can wipe out your exit, even in a win.

- Governance blind spots: Control matters. Review board structure, veto rights, and decision-making power just as carefully as the money.

- Clause creep: Not all boilerplate is harmless. Anti-dilution, clawbacks, and long no-shop periods often hide in the fine print.

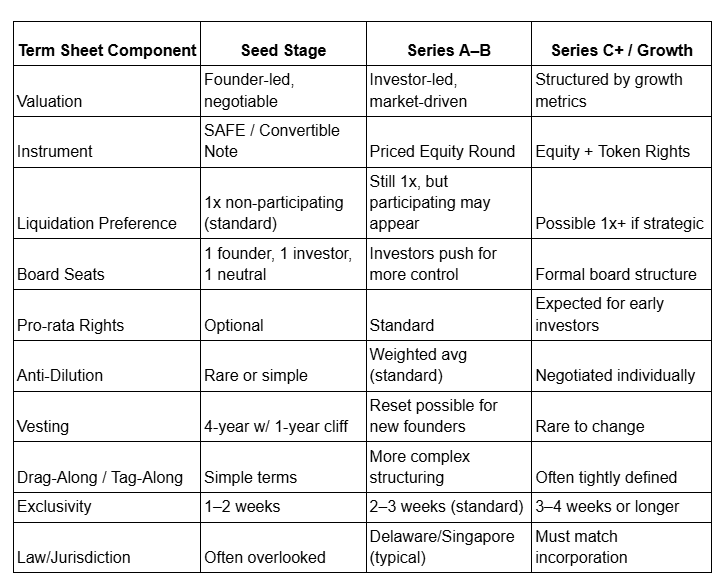

Examples of Term Sheets in Practice

Term sheets shift with stage, structure, and who’s holding the pen. But patterns do emerge. Here’s what typical terms look like:

What’s normal in Term Sheets, by stage

Term sheets evolve as you grow. Here's a quick guide to what’s standard at each major funding milestone, so you know what’s reasonable and where you might want to push back.

Note that “Normal” is context-dependent. Use this as an orientation and not the gospel. If a term feels off for your stage, ask why.

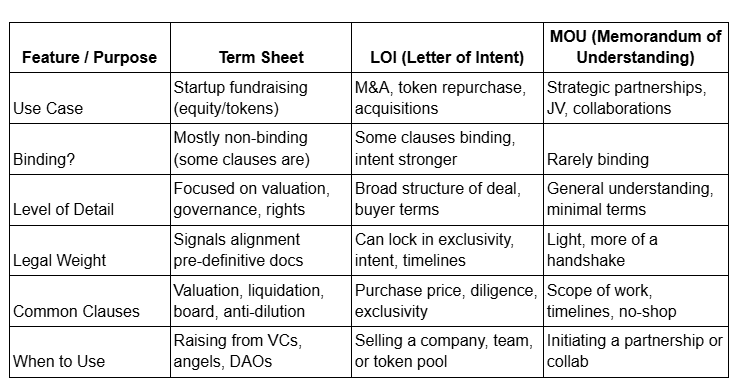

Term Sheet vs LOI vs MOU: What’s the Difference?

These three documents often show up early in deals, and often get confused. Let’s break them down.

Which One Do I Use?

- Use a Term Sheet if you’re raising capital (equity, token, or hybrid). It’s designed for speed and clarity in fundraising.

- Use an LOI if you’re negotiating a sale, acquisition, or buyback, especially when exclusivity or diligence access is needed.

- Use an MOU when exploring a strategic alliance or partnership, where both sides want to get aligned before diving into deeper terms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a term sheet legally binding?

Not entirely. Most business terms, like valuation, equity split, and governance, are non-binding. But clauses like confidentiality, exclusivity, and governing law are often binding. Read carefully.

What happens after a term sheet is signed?

You move into due diligence and the drafting of definitive agreements (e.g., SPA, SHA, token agreements). If both sides stay aligned, the deal moves to closing.

Can a founder walk away after signing a term sheet?

Yes. If the term sheet is non-binding, you can walk. But expect reputational impact if done in bad faith. And if you’ve agreed to exclusivity or no-shop clauses, walking away prematurely could breach those.

Do angels use term sheets too?

Yes, especially when writing larger checks or leading rounds. That said, in early stages (friends & family, pre-seed), investors often use SAFEs or convertible notes instead of formal term sheets.

What’s the difference between a term sheet and an MOU?

A term sheet is built for fundraising. An MOU is broader and typically used in partnerships or exploratory agreements. MOUs carry less legal structure and fewer defined economics.

Do I need a lawyer to review a term sheet?

Yes. Even though it’s not a final contract, the precedent it sets is powerful. A lawyer can spot red flags (especially in liquidation, board control, anti-dilution) and protect your leverage down the line.

Download the GVRN Term Sheet Readiness Checklist

Before you sign, share, or send your next term sheet, run it through our founder-first checklist.

[Download the Notion Template / Interactive PDF] (Insert link here)

Final Thoughts: Term Sheets as Founder Leverage Tools

A term sheet is your first real chance to shape the deal and set the tone for how your company grows.

It tells you:

- What the investor prioritizes

- How much control they’re asking for

- How your cap table might evolve over time

Most importantly, it gives you leverage, if you know how to use it.

At GVRN, we don’t believe in defaulting to “standard terms”, especially for Web3 companies. Founders should understand each clause, challenge what doesn’t fit, and negotiate with clarity. That’s how you protect your ownership, your team, and your time

.png)

.png)